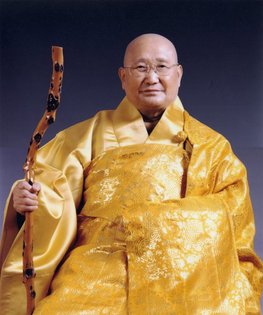

Today is Zen Master Seung Sahn's birthday, and because Lotus Heart Zen wouldn't exist if it weren't for Zen Master Seung Sahn's teaching, I devote this post to honoring his life. Here is a short, I am certain, incomplete biography of his life, based on readings and what I have learned from his many students. (I apologize for any mistakes that I might have made in writing this.) Seung Sahn he was born in 1927 as Duk-In Lee in South Pyongan Province of occupied Korea (which is now North Korea) and was raised in a Presbyterian family. Korea, at this time, was under a very restrictive Japanese Empire rule where all political and cultural freedoms strictly limited. He became concerned about freeing Korea from the grip of the Japanese and when he was only 17 years old, he joined an underground independence movement. Unfortunately, a few months later, he was captured and imprisoned by Japanese police and only narrowly escaped a death sentence. Imprisonment didn't squelch his ambitions to fight for Korea's independence, after his release from prison he and some of his friends headed out, crossing into Manchuria, in order to join the Korean Liberation Army. They were unsuccessful in their ambitions and returned home. After end of World War II Seung Sahn attended Dong Guk University and studied western philosophy. Despite the end of the war the political climate in South Korea continued to be very unstable. Through his education and political activities, he sought to learn how to help the suffering that was going on in his country because of this instability. He had become friends with a monk who attended University. The monk gave him a copy of the Diamond Sutra, a major text for Mahayana and Zen Buddhism. One day, after reading the Diamond Sutra, he found a particular passage spoke deeply to him: "All things that appear in this world are transient. If you view all things that appear as never having appeared, then you will realize your true self." Pondering this passage, Seung Sahn came to believe that his education and political involvements were not going to help others. He decided to leave school and become a Buddhist monk. In 1948, he shaved his head and received pratimoksa precepts--becoming an ordained monk. Ten days after his ordination, he went into the mountains and preformed a 100 day solitary retreat. He chanted the Great Dharani for 20 hours a days and took daily ice baths. He reputedly survived during that time only on pine needles, dried and pounded into a tea, and rain water. He emerged from that retreat awakened. He then left the mountain retreat in search of a teacher who could confirm his awakening. He met Zen Master Kobong who was considered to be the most brilliant Zen Master alive in Korea at the time. He was known for his eccentric and spontaneous style of teaching. He was also a very strict teacher and had yet to grant transmission to any students, as he believed the monks were too lazy and didn't practice hard enough. Upon meeting Kobong, Seung Sahn tested the Zen Master by asking him a series of questions that lead to a lengthy interchange. Finally, Kobong asked Seung Sahn: “A monk once asked Zen Master Jo-ju, “Why did Bodhidharma come to China?” Jo-ju answered, “the pine tree in the front garden.” What does this mean?” Seung Sahn understood what Kobong was asking, but he was at a loss for how to give an answer. So he replied, “I don’t know.” Kobong said, “only keep this don’t-know mind. That is true Zen practice.” Thus began Seung Sahn’s Zen training. He went to sit a winter kyol che at Sudeoksa, the head temple of the Jogye order. During the retreat, Seung Sahn believed the monks weren’t practicing hard enough, so he decided to cause some mischief. He secretly set cooking utensils out in the monastery yard, turned the Buddha statue to face the wall and hung a priceless incense burner in a tree. The monks were in an uproar trying to figure out what was going on. On the third night of his pranks, he snuck into the nun’s quarters and took 70 pairs of shoes and put them outside the door to Zen Master Dok Sahn’s room. But Seung Sahn was caught by a nun and he had to face the monks and nuns for a trial. The nuns found him guilty, but the monks voted to give him a second chance, and was instructed to apologize personally to all of the senior monks and nuns. In middle of January of 1949 Seung Sahn received Inga from Zen Masters Keumbong and Keum'oh. However, when he met later with Kobong, he was challenged by the Zen Master, until Kobong was satisfied that he was indeed awakened. Ten days later, Seung Sahn, at the age of 22, received transmission and became the 78th ancestor in the line of succession. This was the only transmission that Zen Master Kobong ever gave. In 1953 he was drafted in the Korean Army and served as a chaplain and then as a captain for nearly five years. In 1957 he took over the role of abbot of Hwagaesa Temple from Zen Master Kobong. During the next ten years or so, Seung Sahn established Buddhist temples in Hong Kong and Japan. While in Japan, he learned about the koan practice of the Rinzai School. In 1972, he arrived in Providence, RI, with little to no English language skills, eventually finding work as a laundromat repairman. A professor from Brown University discovered, to his surprise, that a Zen Master from Korea was working at the laundromat. The professor helped direct Seung Sahn to learning English. Seung Sahn worked hard on his English language skills and eventually found students to work with at nearby Brown University. In 1974, he began to establish Zen centers throughout the US, beginning with the Dharma Zen Center in LA. This Zen center was unique in that it was a place were lay and ordained practitioners could practice and live together. Then followed a succession of Zen centers being established throughout the US and Europe. In 1983, he started the Kwan Um School of Zen. While still keeping some of the traditional Korean Seon practices, Kwan Um also included Pureland, Chan and Huayan practices. Some of the singular aspects of Kwan Um was that laypeople wore the robes of full monastics, didn’t require celibacy, and had rituals and practice forms unique to the school. Seung Sahn also insisted on women holding leadership positions in Kwan Um--which at the time were usually reserved for men. During his years of teaching, Seung Sahn appointed many dharma heirs. After some arguments with the Jogye order in Korea, regarding the status of lay practitioners and their titles and the robes, he created the title Ji Do Peop Sa Nim (JDPSN) for senior teachers who had not yet realized full dharma transmission. His teaching style was unique. Partly due to his poor English language skills, his teachings were given in simple and direct phrases, but often delivered with humor and charm. His method of delivery, made him an accessible teacher to the Western audience. However, despite his disarming charm, he still managed to instill a strict and rigorous practice of sitting and longans As he primarily taught in the days before the personal technology boom and the internet, he used his correspondence to students through hand written letters as an opportunity to teach the dharma. He encouraged his students to develop “together practice” which utilized the practice centers as a place to come together and practice as one. Zen Master Seung Sahn had a series of often used phrases that he centered his teachings around: “Don’t Know”, “Only go straight”, “Attain no attainment.”, “Open mouth, first mistake.”, “Don’t make anything.”, “Try, try, try, 10,000 years.” “Only just like this.” He used these phrases over and over, sometimes even to some of his student’s chagrin: A senior student who had been practicing with Seung Sahn for many years was walking with his teacher along a hallway. When the master, in response to some item in the conversation, advised his for the umpteenth time, “Only don’t know,” something in the student snapped. Grabbing his teacher and shoving him up against the wall, the student shouted “If I hear you say that one more time I’m going to scream!” Seung Sahn looked at him and nodded. “Very good dharma demonstration!” he said. He had an irreverent, outrageous style that simultaneously confused and compelled those who heard his talks. He developed is own program of study for kongans (koans) that he called the 12 gates. They were comprised of ancient kongan forms as well as new kongans that he created. At the time of his teaching in America, zazen—sitting practice taught primarily from the Japanese styles--had taken hold and was well rooted to Zen practice in America. Seung Sahn's background didn't emphasize sitting practice as rigorously as the Japanese, however, at the student's request, he began to incorporate sitting practice as part of the Kwan Um style, as it was clear that zazen and Zen had become inseparable in the West. Through most of his years in the west Seung Sahn struggled with diabetes and heart complications. In 1990 he was invited to the Soviet Union by Mikhail Gorbachev and he made frequent trips there to teach. In 1999 he opened the Tel Aviv Zen Center. However, by that time, his health had deteriorated greatly. As a result he traveled less and less, As he became more frail, Seung Sahn stayed at Hwagaesa Temple in Seoul, South Korea. However, because of continuing friction between the resident Jogye monks and the Kwan Um monks and laypractioners who frequented Hwagaesa, Seung Sahn sought to establish a temple for Kwan Um in Korea. In 2000 the new Zen Center and temple was established. It was named Musangsa and became home to the Seung Sahn International Zen Center. He had a pacemaker implanted in 2000 and in 2002 he experienced renal failure. Because of continuing friction between the resident Jogye monks and the Kwan Um monks and laypractioners who frequented Hwagaesa, Seung Sahn sought to establish a temple for Kwan Um in Korea, which was named Musangsa and established the Seung Sahn International Zen Center. In 2002, the World is a Single Flower conference, a triennial international gathering of practitioners started by Seung Sahn in 1987, met at Musangsa. It would be his last time attending the conference. In June 2004, the Jogye Order in Korea awarded him the honorific Dae Jong Sa “Great Lineage Master”, for all the accomplishments he had achieved throughout his life. This is the highest title the Jogye order grants. A few months later, on November 30, 1004, Seung Sahn, at the age of 77, passed from this life at Hawgaesa Temple. His presence and influence is still felt by the many practitioners he encountered during his life. I am fortunate to be the student of two teachers who were themselves, students of Seung Sahn. Their efforts to continue teaching the dharma, honoring all that Seung Sahn gave to them by passing his teachings on is palpable and appreciated greatly. I attended the World is a Single Flower conference in 2002, traveling to South Korea with my first teacher MyoJi Sunim. I saw a man who was very frail and weak in body, but his effort to attend the conference, to be present for all who came, was a clear demonstration of his tremendous compassion. One day, while at Hwagaesa, I was called from my room by MyoJi. She lead me out to the courtyard and instructed me to go into a small building that rested next to the main Dharma hall. I had learned by that time not to ask what I was to do, but to just do what she said. So I entered the building completely unsure what to expect. I walked into what appeared to be a miniature dharma hall, a room really. To my left on a raised platform sat Seung Sahn. Immediately I fell to bowing before him. He waved his hand, indicating that I stop. I sat, unsure what to do or what to say. He asked me, "You enjoy stay here?" "Oh, yes, very much." I said enthusiastically. A long pause. Then he asked me,"You happy with practice?" I replied, "I find it challenging, but that doesn't bother me. MyoJi has helped me very much, I am grateful to accompany her on this trip." Seung Sahn nodded. "Listen to MyoJi, she teach you well." He then told me to go get MyoJi as he would like to talk with her. I spent the rest of that day a bit in a daze. I had never expected I would get to speak with Seung Sahn, and to this day, that short meeting has stayed with me. Despite being gravely ill, he made an effort to meet and speak with me. I saw, in those brief moments, the clarity and kindness that my teachers and others who have met with him spoke often about. It will be a moment in my life that will always stand out. Happy Birthday Zen Master Seung Sahn. You continue to live on through the many people whose lives you touched!

1 Comment

|

A blog by the Lotus Heart Zen Meditation and Study Group members

Practice SchedulesArchives

June 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed